There can be few who have walked among the old stone buildings of French towns and villages and not felt the ghosts of history guiding us along the cobbled streets. They have inspired some to write successful novels and travel guides, but for me, what started as an exercise in French translation turned into my quest to understand the origins and the development of our adopted village along with a greater understanding of France and her people.

With the help of several villagers we have put together this collection of photographs. As you can see they are mostly from postcards, commonly sold in the local shops and cafes at the beginning of the twentieth century. We have attempted to match them with the same view taken shortly after we settled in the village in 2007, a time span of roughly one hundred years. We went on to discover how the development of Champagny-Sous-Uxelles dated back to the French Revolution of 1789

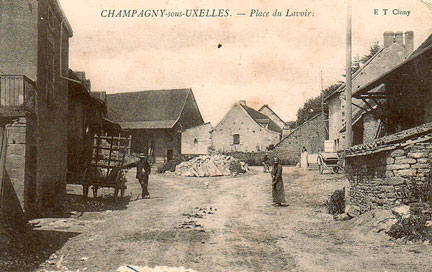

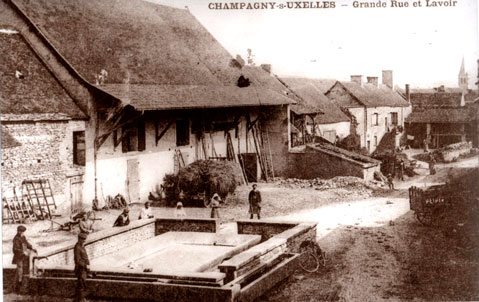

A Village Scene

Looking up the main street towards the crossroads where the "lavoir" was situated.

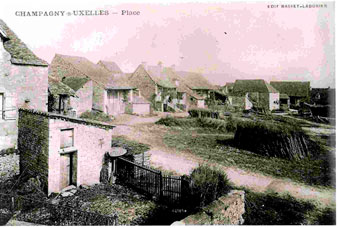

Place De L'Êglise

The view from our first floor window.

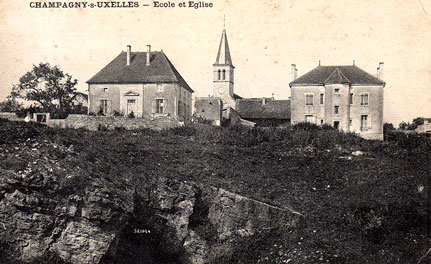

School, Church and Presbytery

From the old stone quarry (in the foreground)

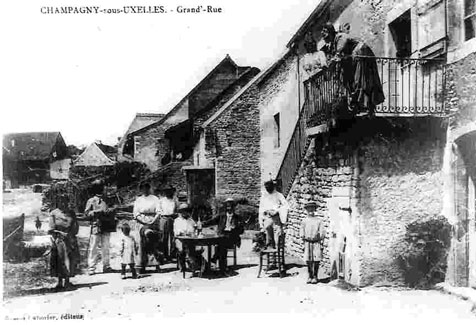

The Main Street Again

Looking down towards the church. This was one of the village cafes.

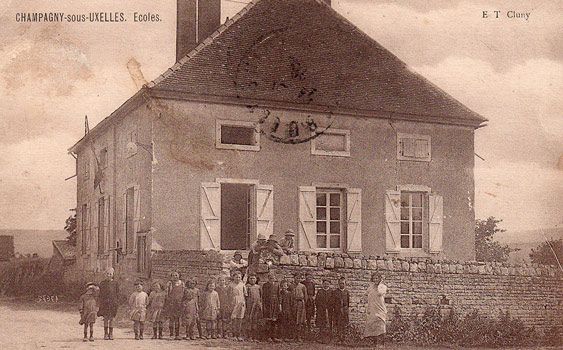

School and Mairie

Children on parade outside the School

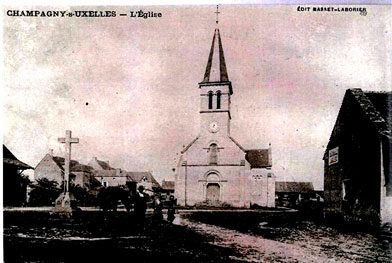

The Church

Between the cross and the church you can just see the original row of dwellings.

The 'Lavoir"

The old Lavoir use water from the spring.

A SHORT HISTORY

There is evidence of occupation dating back to Roman times, but Champagny was reduced to the rank of a hamlet belonging to the commune of Colombier-Sous-Uxelles along with Colombier-le-Bas, Colombier-le-Haut and Forgeuil which were all on the north-western side of the hill. Until the 1789 revolution, the small and lonely community of Champagny, probably aided by a few monks, scratched a living from its stony southeastern facing slopes.

In November 1789 the newly formed Republican Government confiscated all the land and property belonging to ‘The Church’ along with some estates of the Royalists. This was not only an attempt to quell the power of the Bishops and the Aristocrats, but by auctioning off these asserts The Republic had the opportunity to fill the huge gap in the country’s finances. It was easy to sell off the large estates especially as payment could be arranged over a period of some eight years or more. The Local Communes were given charge of smaller parcels of land, woodland etc. to administer for the good of The Republic. Much continued to be rented out, but the commune of Colombier-Sous-Uxelles offered the poor stony land of Champagny for sale.

The ability to purchase land attracted many farmers, mostly wine growers, and the hamlet of Champagny expanded rapidly around the turn of the century. New dwellings, barns and workshops spread down towards the lower part of the village and the woods. This new community prospered and records show that the population grew by 270 between 1793 and 1800 and reached a peek of around 600 souls by the middle of the nineteenth century. Bearing in mind that, at this time Champagny was still part of Colombier-Sous-Uxelles, so that the actual population of Champagny itself is more likely to have been about 300. This is why Champagny partitioned to become the principal commune.

After building its own Church, School and other facilities, the commune of Champagny-Sous-Uxelles was formed in 1893. In 1903, Colombier and Forgeuil, detached from Champagny, became hamlets attached to Bresse-Sur-Grosne.

ADDITIONAL NOTES

It is worth noting that the auctioning off the church lands was a disaster for the Republic. They had created a paper currency known as (les assignats), spacially for this trade but fell into the trap of printing more and more money against their diminishing assets. As a result the money lenders became bankrupt by accepting repayment, all to the advantage of the borrowers who ended up with their land costing almost nothing.

When the monarchy was restored in 1814, many aristocrats were able to regain their lands, but purchasers of former church lands managed to retain it, as was the case in Champagny. Ownership of land is said to be key to agricultural investment, development and subsequent prosperity. Of course the beginning of the twentieth century initiated changes in agriculture as the population was drawn to work in the industrial towns and cities.